Beginning of Licensure

As building technology began to advance in the late 1800s, a series of devastating building failures highlighted the need for standards that would protect the public. In 1897, Illinois became the first U.S. jurisdiction to regulate the profession..

VIDEO: Pre-Licensure in the United States

Learn more about the U.S. built environment prior to regulation—and what convinced legislators licensure was necessary.

The Need for Regulation

Technology and Tragedy

Like many other professions, the building industry was undergoing a period of transformation in the late 1800s. Advances in technology led to new construction materials and methods. By using stronger steel and concrete, as well as newly improved elevators, architects could design structures that were taller, grander, and more ambitious. When done correctly, the results were striking. Skyscrapers began to take over city skylines.

However, taller structures led to higher stakes. With no qualifications required to practice, inexperienced or incompetent individuals could—and often frequently did—design and build structures that led to catastrophic building failures.

Newspaper headlines frequently highlighted horror stories of fires and building collapse. The causes were often linked to poor construction or design, especially a lack of foresight to include safety features that could save lives in the event of an emergency. As the number of fatalities rose with each roof collapse, so did public and political interest in establishing a system that would protect people from low-quality architecture.

Deadly Building Failures

On December 30, 1903, Chicago’s Iroquois Theater caught fire. Over 600 people attending a matinee performance died—many of them children—due in large part to A combination of design choices. Difficult locks on the emergency exits, incomplete fire escapes, and doors opening inward rather than out made the fire difficult to escape; following the fire, city officials quickly ordered fire upgrades to theaters across the city. The Iroquois Theater Fire remains one of the deadliest single-building fires in U.S. history.

The collapse of the District of Columbia’s Knickerbocker Theater in January 1922 was due to similar oversight. When 26 inches of snow accumulated on the theater’s roof, it caved under the weight, killing 98 and injuring 133. Investigation revealed that the roof support had not been properly designed.

Fueled by these tragedies, architects began to call for legislators to pass health, safety, and welfare legislation that would protect the public from incompetence and fraud.

“The people want protection, and it is the duty of the state to give it to them.”

The Rise of Professions

Architecture was not the only profession struggling with the impact of technological advances brought on by the Industrial Revolution. Andrew Jackson’s presidency in the 1820s and his push to promote the interests of the “Common Man” against the restrictions of bureaucracy had reduced many of the relatively few professional regulations existing at the time. Professions like medicine and finance found themselves inundated with uneducated practitioners who were endangering the public.

As a result, many groups began forming professional associations, with the goal of encouraging states to establish standards for practice. The American Medical Association was founded in 1847, a decade before the American Institute of Architects’ (AIA) creation in 1857; lawyers, nurses, pharmacists, and accountants created their own organizations in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Together, these individuals began lobbying their state legislators to uphold their duty to the public by creating laws that would prevent fraud and incompetence.

The First License Law

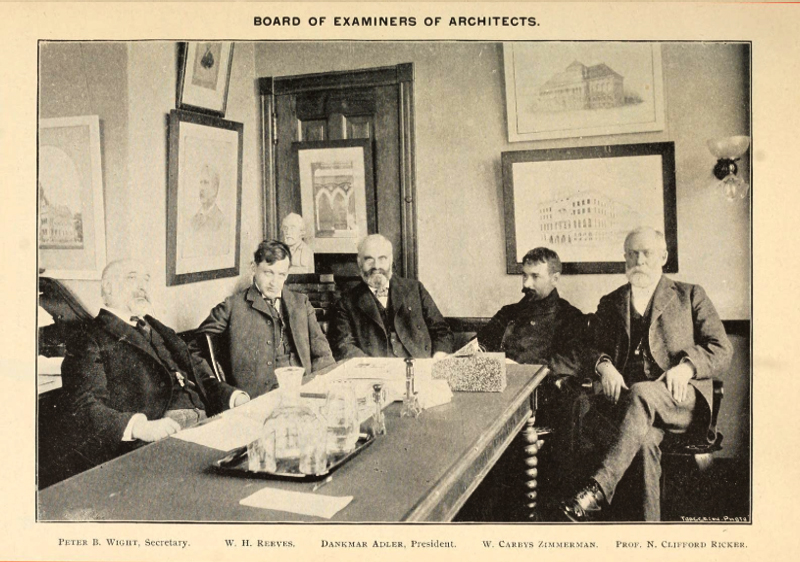

In 1884, architects from the Midwest and South created the Western Association of Architects (WAA), frustrated by the slow speed of AIA’s larger membership. The WAA was the first organization to seek architecture licensing laws. By the time of the group’s second meeting in 1885, Chicago architect Dankmar Adler had drafted a bill, which WAA members could present to legislators for adoption.

The success of other new regulations gave the WAA members confidence: throughout the late 1800s, states passed more than 1,600 laws designed to ensure the safety of their inhabitants. If they could demonstrate enough public support, the architects expected the legislative process to go smoothly.

“Our legislators never consider a matter that is not urged upon them by their constituents. They’ll pay but little attention to a little committee of architects who come with a bill from their professional association.”

Getting a bill through state legislature proved more difficult than anticipated. Texas architect Wesley C. Dodson was a steady advocate for licensing laws; in 1889, a bill he advocated for came close to passing, but was never finalized.

Similar situations happened in New York, California, Missouri, and Ohio. Proposed bills fell to the legislative backlog or were considered an attempt to limit competition.

Adler and his fellow Illinois architects drafted bills in 1887, 1889, and 1895, failing each time. With the help of an architect newly elected to state legislator, a licensing law was proposed again in 1897—and it passed. On July 1, 1897, Illinois became the first U.S. state to require licensing for architects.

In the Public Interest

Following Illinois’ success, architects in several states initiated or renewed efforts to convince their legislatures to enact a similar law. California and New Jersey were quick to follow, establishing architectural regulation boards in 1901 and 1902, respectively. Architects in New York tried again in 1901, 1905, and 1909, before finally succeeding in 1915.

“To license a man to practice a profession is to grant permission to him, due to his special knowledge and equipment, to do that which common sense dictates others must not do.”

Meanwhile, building failures continued to make newspaper headlines. In some states, these incidents caught the public attention, leading to demands for oversight and regulation. But in others, critics pointed out that paying a licensure fee did nothing to ensure that architects were competent.

The question of competency was a common concern to the architects who pushed for regulation. As more jurisdictions enacted licensure laws, discussions regarding how to best determine an applicant’s qualifications came up frequently at AIA conventions—especially when the architect was coming from a state with lower or no standards.

By 1911, it was clear that an intervention was needed to help boards adopt uniform standards. But who would determine and encourage those standards? Over the next eight years, the idea grew and took shape, planting the seeds for NCARB’s formation in 1919.

Note:

- Header image provided by University of California, Riverside; Riverside, CA

- Wesley C. Dodson image provided by Dodson's family

- Dankmar Adler image provided by the Ryerson and Burnham Libraries, The Art Institute of Chicago Ryerson and Burnham Libraries, The Art Institute of Chicago