Creating NCARB

Since NCARB’s formation in 1919, the organization has undergone significant restructuring to ensure staff kept pace with the evolving needs of both Member Boards and customers.

VIDEO: FORMATION OF NCARB

In 1919, 15 architects from 13 licensing boards formed an organization to set national standards for licensure and reciprocity.

NCARB's Formation

The Early Years

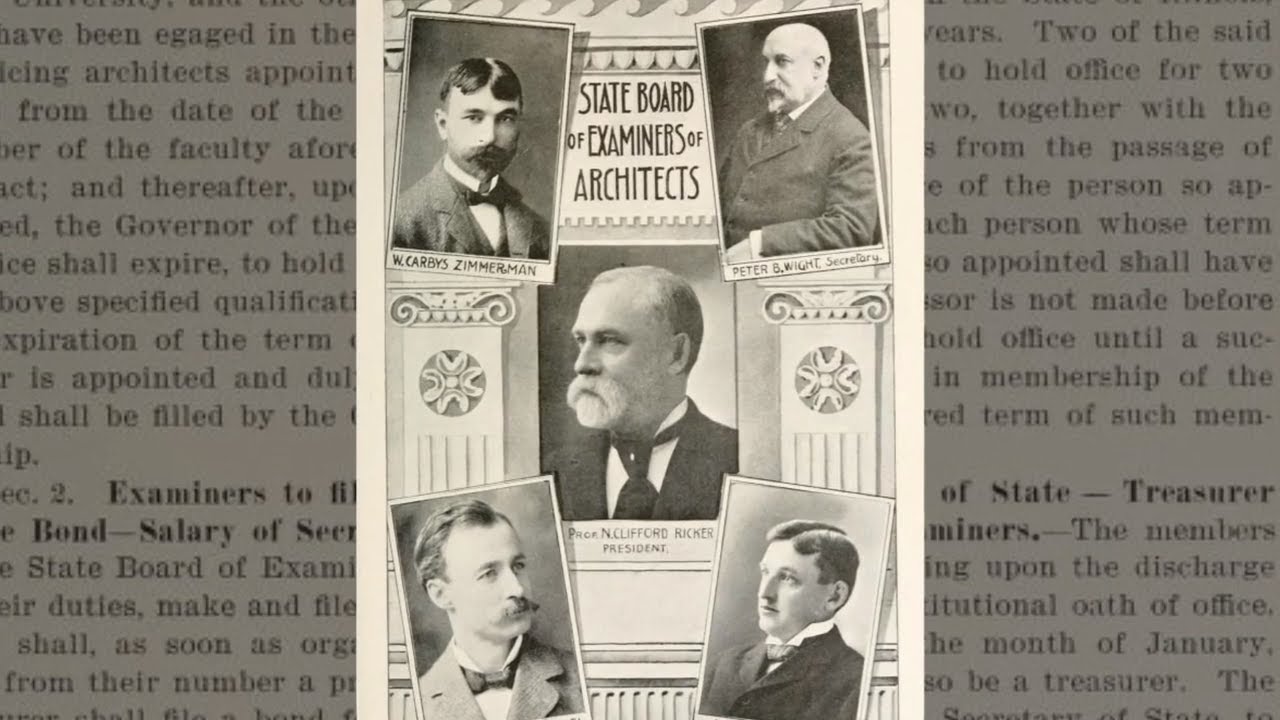

In the short time since the nation’s first licensing laws were created in the late-1890s, board members already had their hands full administering examinations and reviewing applications to license architects. By 1919, nearly 20 states had architectural registration laws, and more were considering legislation. However, rules varied widely across jurisdictions, and boards were hesitant to process applications for out-of-state architects—especially if the architect practiced in a state with inferior (or no) standards.

Concerned with this growing trend, Illinois architect Emery Stanford Hall invited colleagues attending the 1919 American Institute of Architects (AIA) Annual Conference to discuss common issues—namely, setting standards for licensure and reciprocity. At a hastily arranged luncheon in Nashville, 15 architects from 13 states put their heads together and sketched out a plan for a new organization. By the close of the meeting, Michigan architect Emil Lorch was selected as chairman and Hall was named secretary. Although it wasn’t until the group met again in 1920 that Lorch was elected president and the budding organization agreed on a name: the National Council of Architectural Registration Boards.

Establishing Operations

The Council’s first formal meeting took place in Washington, DC, on May 5, 1920. Several months later, Hall drafted the Council’s original Constitution, which outlined the organization’s core purpose: “to foster the enactment of uniform architectural laws and uniformity in examinations of applicants for state registration or licensure.”

The administrative costs associated with fulfilling these goals was another hurdle entirely. NCARB officially launched its finances in January 1920 when President Emil Lorch opened a checking account at the Great Lakes Trust Company of Chicago with a deposit of $101.50. In 1921, Hall helped get the organization off the ground by setting up shop in his Chicago office, acquiring a $300 loan from the Illinois Society of Architects, and even providing money out of his own pocket. NCARB’s success over the next decade was gratifying, but also created mounting administrative responsibilities. The organization realized that the model of a single administrator was unsustainable and additional resources were needed.

“Unless the revenues of the Council from investigations and reports can be increased, there is grave danger that we cannot continue to carry on.”

By 1932, the tiny NCARB office was hit hard by falling revenues and the stalled economy. At the 1943 Annual Meeting, Executive William L. Perkins urged attendees to consider becoming “sustaining members” for an annual fee of $10. Several years later, Lorch was blunt about the need to look for external sources of financing—at least in the short term. Appeals to the Carnegie Corporation brought in several thousand dollars to defray salaries and printing expenses, but only for two years. Generous gifts from at least two anonymous benefactors helped to shore up the bottom line during the worst years of the Depression.

When World War II ended, the nation’s building industry boomed. With a generation of architects returning from overseas and relocating throughout the country, NCARB was inundated with requests—and NCARB’s small staff was overwhelmed.

Growing Pains

After Hall’s passing in 1939, the NCARB office relocated from Illinois to Iowa under the stewardship of Perkins, who led the Council’s work for 18 years. When Perkins died from a heart attack in 1957, the Council’s headquarters moved again to Oklahoma when NCARB’s new Executive Joe E. Smay took the reins. But by the late-1950s, the organization was simply too big to be packed into a crate and shipped around the country. Cramped office space in Oklahoma City only exacerbated the problem of managing thousands of files, dealing with a growing backlog, and processing new requests for service.

When serious illness forced Smay to step aside in 1959, new incumbent James Sadler walked into an office that was on the verge of a breakdown. According to 1962 President C. J. “Pat” Paderewski, Sadler “worked day and night” to overhaul how Council staff reviewed applications and processed annual renewals. In December 1962, NCARB took the opportunity to move closer to its collateral organizations in Washington, DC, opening its new office in January 1963.

Still overwhelmed by a growing backlog of customer requests, NCARB staff were off to a rocky start in the nation’s capital. Sadler and longtime administrative assistant, Anna Ruth Lucas, threw themselves into the task of interviewing, hiring, and training new employees, while temporary secretaries were brought in to keep the wheels turning. A handful of licensing board members volunteered to help evaluate Council Records, while others offered to plan the next Annual Meeting.

The move vividly demonstrated the need to transform NCARB into a more sophisticated organization, managed and staffed by professionals. With the Board of Director’s blessing, Sadler hired Richard V. Scacchetti as NCARB’s first administrative director. Within his first year, Scacchetti was able to report progress in reducing the backlog of Certificate applications and Record transmittals, as well as reorganizing NCARB’s operations. The Council hired three new staff members and processes were streamlined.

The growing pains of the first four decades slowly faded as NCARB settled into its new Washington, DC, home. Taking a more business-like approach to the Council’s activities was a sign of how far NCARB had come since its earliest days. The organization now had a savings bond fund worth more than $100,000—a respectable cushion and a far cry from Lorch’s original $101.50 deposit. NCARB finally had a structure that provided resiliency and stability. The economy was strong, and Member Boards were using and aligning to the Council’s programs.

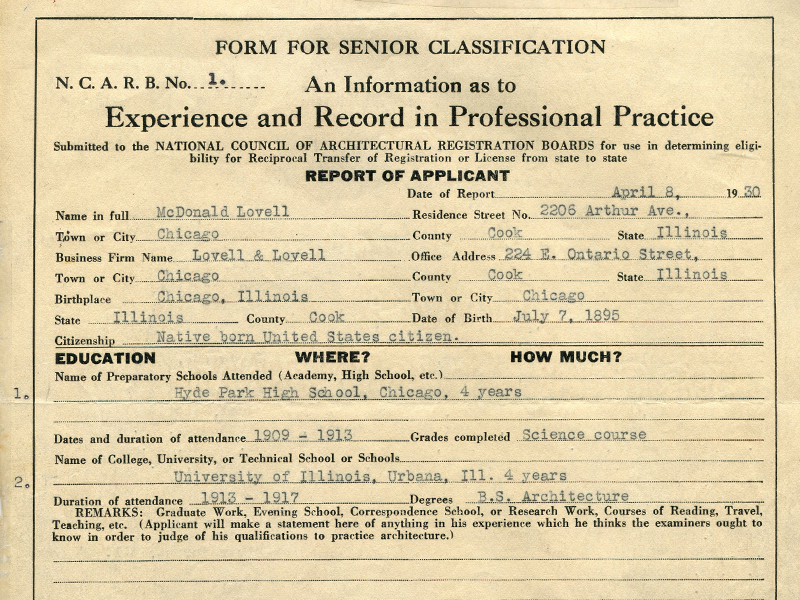

A Centralized Record

As the demand for reciprocal licenses grew, board members were soon inundated with inconsistent and unreliable paperwork from other states. In 1920, Vice President Arthur Peabody suggested the Council develop a standardized, verified form that would streamline the application process. Peabody’s suggestion for a formal record-keeping system was implemented immediately. The newly launched Council Record enabled NCARB to serve as a clearinghouse for architects’ professional history—documenting their education, work experience, examination results, and references. Although it wasn’t until the 1930s that the organization introduced the NCARB Record customers know today.

The convenience of a centralized service for compiling and maintaining detailed credentials helped introduce American architects to the new organization. In its first year, NCARB staff handled 45 applicants for reciprocal transfer and 19 candidates seeking to take the NCARB Examination. During the 1939 Annual Meeting, Leonard H. Bailey of Oklahoma said that Council Records “cover the ground so thoroughly, they give you such a complete picture, not only of the ability of the [applicant] but also of [their] respectability.”

Bailey’s comments were exactly the validation of NCARB’s services that Hall and his colleagues had in mind when they envisioned NCARB. The Council’s ultimate goal was not simply to cut through red tape, but to build up a trusted national system of standards and processes that would unite and elevate the entire profession. Around the same time, the organization began designing a Certificate to award architects who met NCARB’s recommended standards.

Member Board Alignment

By the late-1950s, all 50 state registration boards had joined NCARB’s membership, as well as the boards of many U.S. territories. As the complexity of the organization grew, licensing boards looked for new opportunities to debate proposed updates to national programs, as well as issues specific to their location. Following several decades of false starts, NCARB’s member boards formed six regions in 1965. Along with NCARB’s evolving examination and streamlined administrative processes, regional meetings helped encourage widespread adoption of NCARB’s uniform standards. Just five years after the regions were formed, all Member Boards accepted NCARB’s examination.

Over time, Council leadership leveraged NCARB’s certification process to draw the profession together to explore how to prepare for the future. Goals were set; projects and studies were undertaken. The conversations were never brief and sometimes contentious. But in the end, out of the thousands of hours of meetings and volunteer work, emerged a commitment to keep talking, pushing, learning, and improving.

Note:

-

Header image: NCARB’s first office was located in Illinois architect Emery Stanford Hall’s practice. From 1922-1927, it was located in the Steinway Hall building in Chicago. Ryerson and Burnham Libraries, The Art Institute of Chicago.

“NCARB’s most significant contribution has been and will always be creating a national standard for licensing architects.”