Education

The rise of interstate practice prompted NCARB to take a closer look at American architecture schools and recommend standardized curricula, eventually leading to the foundation of the NAAB in 1940 and the adoption of the degree requirement in the 1980s.

VIDEO: HISTORY OF EDUCATION

Explore NCARB’s role in the evolution of architectural education standards, including the establishment of the NAAB-accredited program.

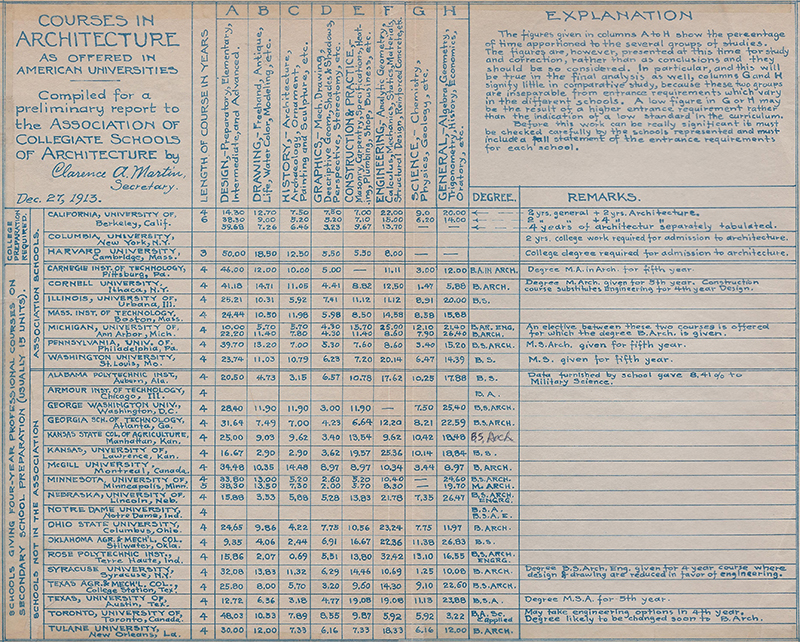

Creating Uniform Curricula

Early Architectural Education

In 1853, the Polytechnic College of Pennsylvania opened the first architecture degree program in the United States. By the time of NCARB’s founding, there were more than 25 schools offering degrees in architecture—an alternative to the previous “apprenticeship” model of training to become an architect.

“The profession is pleased to call itself a learned profession. If this assumption is to be supported, then it is paramount that broad and high standards of qualifications shall be maintained.”

As jurisdictions began to set requirements for licensure, the vast differences in educational rigor, style, and content across the various programs became increasingly apparent. Also apparent was the lack of an organization to establish standards at architecture programs. The Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture (ACSA), founded just a few years before NCARB, published a recommended Standard Minima for programs to aspire toward, but could not enforce it. Similarly, NCARB and its Member Boards could set education standards for licensure, but had no authority to make schools offer programs that met those standards

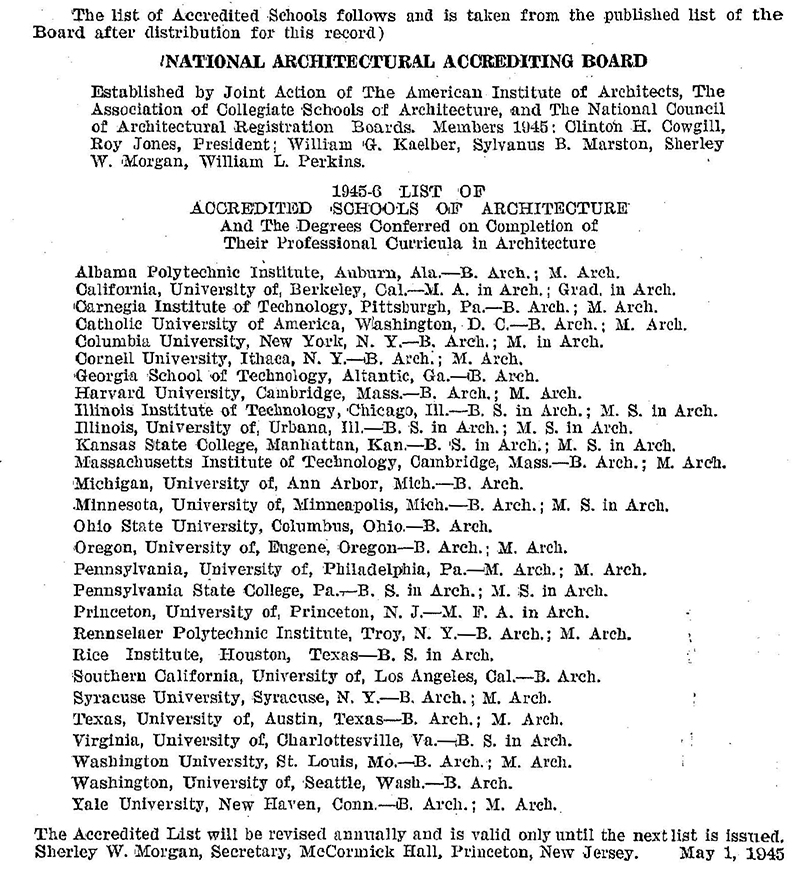

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, NCARB’s membership debated what level of education should be required for licensure, as well as for admission to NCARB’s exams. Some members felt that a thorough education was a key step in becoming licensed, while others felt that an education standard would make the profession too difficult to enter. Plus, boards were unsure which programs were acceptable. In 1932, NCARB began releasing a regular list of approved colleges for licensing boards to use. However, the Council lacked a consistent evaluation process, and when the ACSA proposed the creation of the National Architectural Accrediting Board (NAAB) in 1939, NCARB’s membership quickly agreed.

The NAAB was founded in 1940 by NCARB, ACSA, and the American Institute of Architects (AIA), which agreed to supply financial support and an equal number of representatives to serve on the NAAB’s Board of Directors, but otherwise take a hands-off approach to NAAB’s day-to-day operations. In 1945 the organization released its first list of accredited programs, and in 1950 it established the five-year Bachelor of Architecture requirement that still exists today.

Education Requirements for Certification

After the establishment of the NAAB, the Council’s next education-related debate regarded whether a degree from a NAAB-accredited program should be required for NCARB certification. The tradition of substituting practical experience in lieu of formal education had long been accepted in the architecture profession, and some architects thought requiring a degree would make licensure out-of-reach for some candidates. Proponents of the degree-requirement argued it was necessary for public safety.

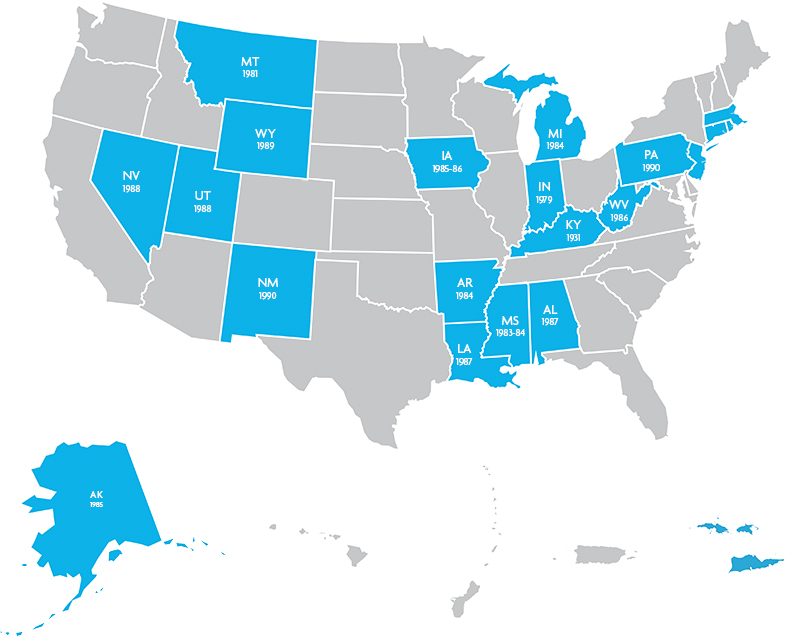

The issue was raised at Annual Meetings throughout the 1960s and 1970s, with a resolution passed in 1967 and overturned in 1968. But in 1980, licensing boards revisited, and passed, a resolution requiring a degree from a NAAB-accredited program for certification, effective 1984.

“Many states are now requiring Bachelor of Architecture degrees ... The certification standard should be as close as possible to or equal to the highest standards set by the states.”

Despite the passed resolution, NCARB’s membership remained divided. To remedy the problem, the 1980 resolution was amended to include a provision for broadly experienced architects, which became the BEA Program. Two years later, the Council released The NCARB Education Standard to help those without the required professional degree understand what they needed to do to qualify for the NCARB Certificate. The Education Standard was based on the student performance requirement established by the NAAB to help potential certification applicants address any deficiencies in their education.

When the education requirement was passed in 1980, Indiana was the only state requiring a degree from a NAAB-accredited program for licensure. Over the next decade, 20 more boards adopted the requirement.

The alternatives for architects without a degree from a NAAB-accredited program evolved over time, including a simplification of the application process and requirements in 2001, and the launch of the Broadly Experienced Foreign Architect (BEFA) Program for foreign architects in 2003.

In 2014, the Council investigated re-engineering the BEA and BEFA processes to make them less time-consuming, less expensive, and more transparently objective. After a resolution failed in 2015, NCARB’s membership approved the new “education alternative” in 2016, to launch in 2017. The new alternative gave architects already licensed in a U.S. jurisdiction a way to satisfy the Certificate’s education requirement—either by completing additional hours within the experience program, or addressing educational deficiencies by completing an online portfolio, documenting learning through experience.

Bridging the Gap: The NCARB Prize

The 1996 publication of The Boyer Report called attention to several issues along the path to licensure—including “the gulf dividing architecture schools and the practice world,” which the report referred to as “perilously wide.”

After several years of a combined effort between NCARB, AIA, ACSA, and the NAAB to bridge this gap, NCARB took responsibility for the initiative in 1999 and launched the NCARB Prize for Creative Integration of Practice and Education in the Academy in 2001. Driven by the vision of then-President Peter Steffian, the Prize’s goal was to celebrate and encourage innovative architecture programs that integrated architectural practice into an academic setting by providing them with additional funding. In 2002, the University of Detroit Mercy was named the winner of the inaugural NCARB Prize, receiving $25,000 for their Detroit Collaborative Design Center.

“The NCARB Prize honors innovative ways of integrating practitioners into the academy in order to expose students to the reality and culture of day-to-day practice,” said Steffian in 2002.

In 2006, NCARB created a companion initiative called the NCARB Grant. While the Prize focused on existing programs, the Grant supported the development of new education initiatives. The Prize was retired in 2011, and the Grant was renamed the NCARB Award in 2012, with a renewed focus on helping schools implement classes, seminars, or studios that would have a long-term impact on students.

Over the course of 15 years, NCARB recognized nearly 100 programs and awarded over $1 million dollars to help the next generation of architects connect education and practice.

Continuing Education

Hand-in-hand with setting rigorous education requirements for aspiring NCARB Certificate holders, the Council tackled the issue of continuing education (CE) for architects already in practice. Keeping up with constant innovations in materials, methods, and building codes required an ongoing commitment to learning throughout one’s career in the interest of public health, safety, and welfare.

The Council’s first study of continuing education began in 1968, and discussion about the prospect of offering and requiring CE continued in the 1970s. However, it wasn’t until 1993 that NCARB began offering CE through its Monograph Series. And in 2011, NCARB’s membership voted to update the Model Regulations’ continuing education requirement to 12 hours in Health, Safety, and Welfare (HSW) topics each calendar year.

Note:

-

Header image: Students at École des Beaux-Arts. Photograph. ca. 1900. Les Collections du Musée national de ’Éducation, file # 1978.02538.2.

- ACSA Chart: Courses in Architecture, As Offered in American Universities, 1913. Print. Courtesy of the Association of

Collegiate Schools of Architecture.