Examination

NCARB offered its first examination in 1921, but it wasn’t until 1965 that a truly national exam was available for licensing boards. Throughout its history, developing and maintaining a current, uniform licensing exam for all jurisdictions has been one of the most complex, and sometimes controversial, of NCARB’s initiatives.

VIDEO: HISTORY OF EXAMINATION

Learn more about the evolution of NCARB’s exam, from the early days to the Architect Registration Examination (ARE) as we know it today.

Creating a National Exam

The Standard Examination

When NCARB was founded in 1919, 19 states had established licensing laws for architects. Each board had its own exam that applicants for initial licensure were required to pass, and many also administered a separate exam to architects who had been practicing at the time the registration law went into place. With no system in place to guarantee each board’s exam measured equal levels of competency, architects who wanted to be licensed in more than one state were forced to test again each time they applied somewhere new.

Solving the exam problem was a key step in making reciprocal licensure an accessible goal, and one of the core reasons for NCARB’s founding.

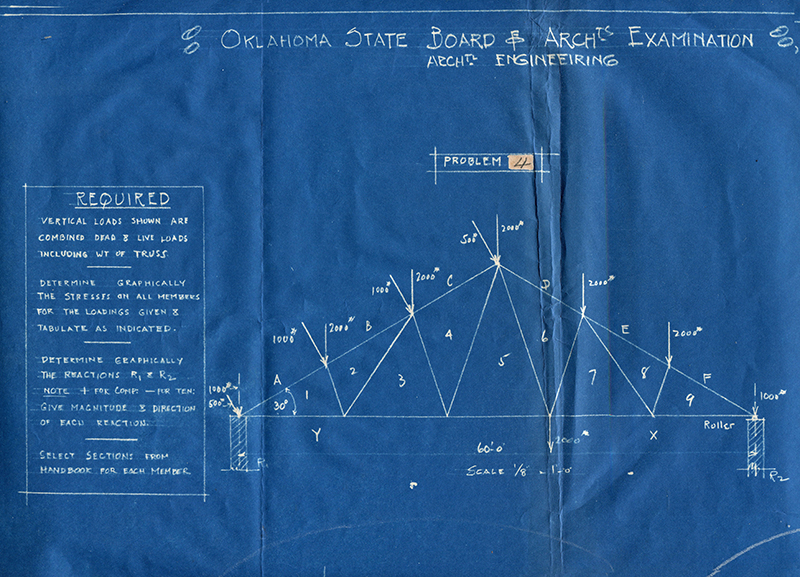

NCARB compared existing state examinations and identified the one with the highest minimum standard. Using this minimum threshold as a measuring stick, the Council then developed the Standard Junior and Senior Examinations, offered for the first time in 1921. Among other topics, NCARB’s examinations tested candidates in areas that states generally did not or could not legally address. Candidates who successfully answered NCARB’s questions, in addition to their state’s licensing examination, demonstrated that they possessed the depth and breadth of knowledge to practice in any jurisdiction.

“It appears to the Council that the most adequate examination is one which discovers, by normal and crucial tests, the skill and competence of a practitioner.”

As time went on, NCARB marketed its examination as an easy solution to the time-consuming problem of tweaking jurisdictional tests to stay in step with changes in architectural practice. The organization offered its members a syllabus that could guide them through determining what to include on their exam.

Throughout the 1930s to 1950s, NCARB attempted various methods of comparing and evaluating the multitude of state exams, including having each jurisdiction submit a copy of its exam for review. However, boards were reluctant to trust the Council’s opinion alone.

“The established yardstick is the Junior NCARB syllabus and it should be the first duty of every state board to take immediate steps to make it the adopted test of their own state.”

Although states and applicants were initially slow to use this service, NCARB’s examination eventually became one of the Council’s most important tools for helping boards facilitate licensure.

The Uniform Examinations

In the late-1950s, the entire field of academic testing underwent a major shift. Multiple-choice questions, which could be graded objectively—and by computers—became the preferred method. In 1954, incoming NCARB President Fred L. Markham suggested that the Council’s new standing Committee on Examinations investigate the “possibility of an objective type of examination which can be checked, if necessary, with an IBM machine.” Members were prepared to adopt the new approach, but realized it required skills beyond those of the average board—as well as a great deal more money and time than most boards had available.

These challenges provided an opportunity for NCARB to step in: by organizing and funding the development of the exam, NCARB could finally offer a truly national exam, while boards would have the benefit of administering a fair, modern, and standardized exam.

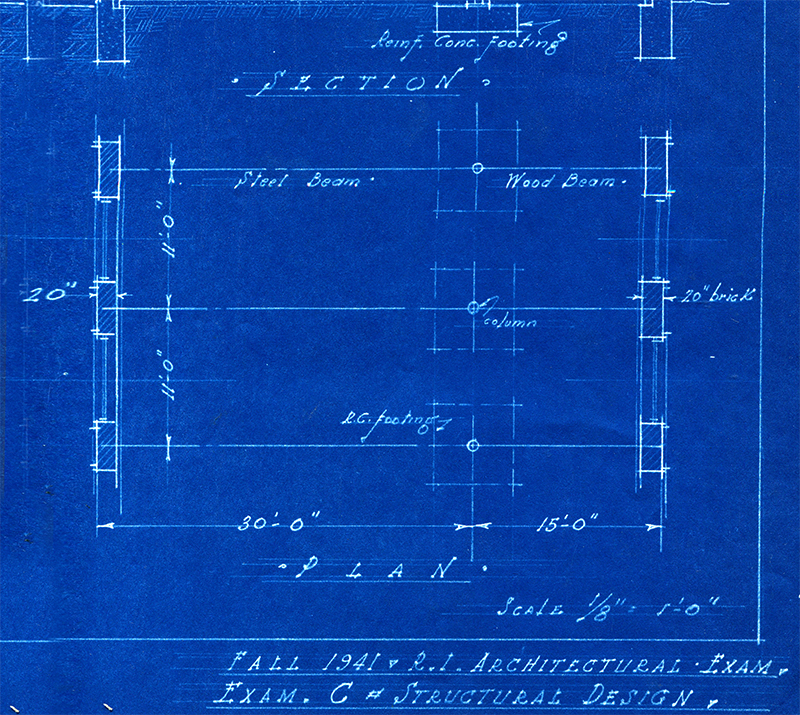

Creating the exam was a massive undertaking that took the rest of the 1950s and into the early-1960s. The exam syllabus had grown to include seven sections, or divisions—five would become multiple choice, and two would continue to require graphic responses on paper. With the help of testing consultant Education Testing Service (ETS) and dozens of volunteer architects, NCARB began to convert the divisions to the new format. The Building Design and Site Planning divisions remained unchanged—both required graphic responses on paper.

The Uniform Examinations were ready for early testing in 1963 and launched nationally in 1965.

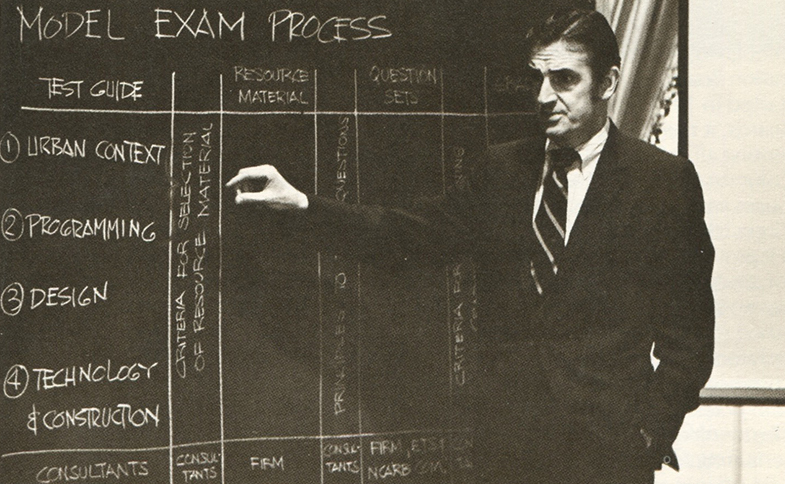

The Professional and Equivalency Examinations

Although NCARB’s membership had settled on a standard examination requirement, inconsistent education requirements across the country impacted the development of the exam. Boards continued to debate how to treat candidates with a degree from a NAAB-accredited program versus those without. Some insisted on an additional examination for candidates without their preferred education background, and felt that candidates with more rigorous degrees did not need to be tested on certain things again.

In 1971, the Council introduced a solution: the Uniform Examinations would be replaced with a Professional Examination for candidates who held degree from a NAAB-accredited program, and the more extensive Equivalency Examination (replaced with the Qualifying Examination in 1976) for those who did not. The chief difference was an additional 12-hour graphic design exam, the precursor to what would eventually become the vignette.

While most candidates were only intended to take one of the exams, many boards required people to take both—and wanted those seeking reciprocal registration to have taken both. This created an extra level of burden for boards and candidates alike.

The ARE Is Born

To satisfy licensing boards and stop the unnecessary—and expensive—testing, the Council used the results of a 1979 task analysis and validation study (today known as a practice analysis) to create one exam for both groups. In 1983, the Architect Registration Examination® (ARE®) was introduced.

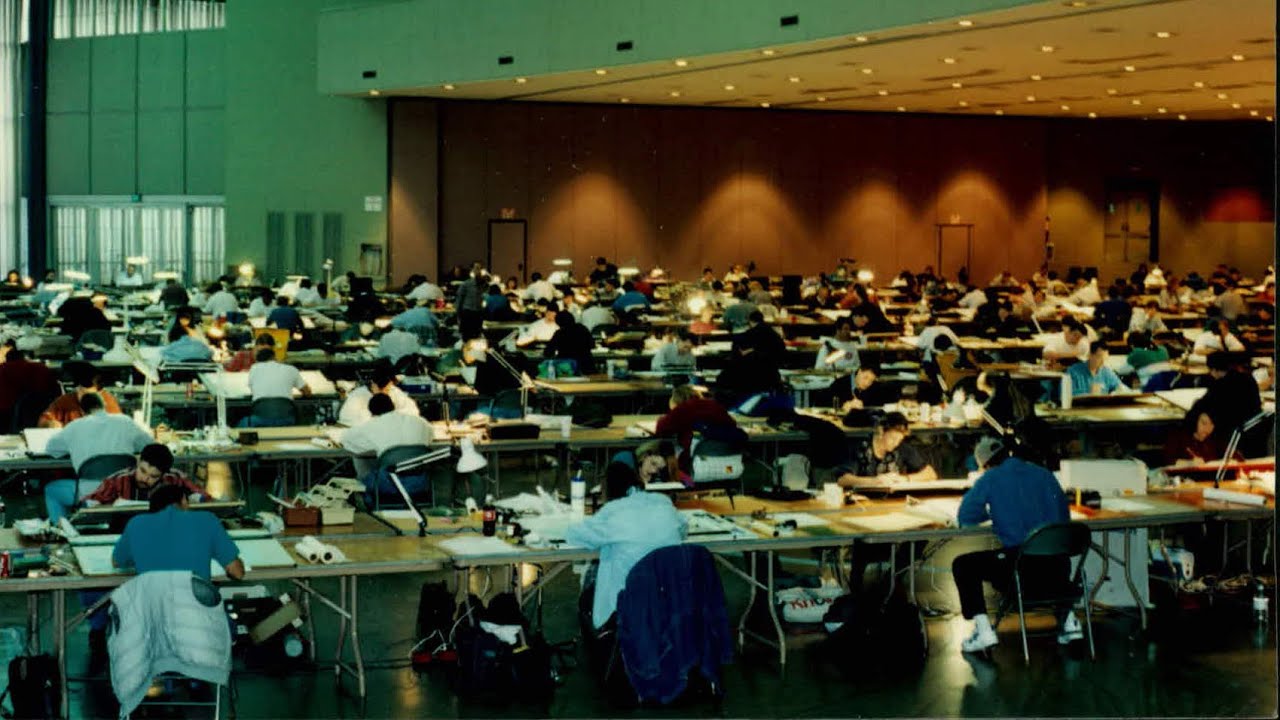

Candidates taking the ARE had to complete 32.5 hours of testing on nine divisions over a four-day period, a major undertaking that required dedicated preparation. Grading the exam was no easy feat, either, and with growing numbers of candidates, boards began to struggle to keep up with the task. In 1986, NCARB introduced national grading sessions. Volunteers from around the country would convene twice a year to score graphic sections. Participating in an NCARB examination grading session became a rite of passage for many NCARB volunteers.

Did you know?

In 1986, the California Architects Board decided to develop its own examination instead of administering the ARE—in part, because its state law still required that design tests be graded by California practitioners; a change that all other jurisdictions had made to support regional grading sessions. The California Board even offered NCARB the opportunity to develop the state’s exam on their behalf.

The California Architect Licensing Examination (CALE) was developed by a local provider and first delivered in July 1987. But architects licensed through the CALE had no pathway to reciprocity.

In September 1987, the California Legislature passed a law limiting reciprocal California licensure to architects whose home state declared the ARE and CALE were equivalent. However, NCARB’s established Bylaws required all licensing boards to administer the ARE to ensure consistency across jurisdictions. A survey of NCARB’s other Member Boards revealed that such a declaration was not feasible.

After lengthy negotiations, NCARB and the California Board reached an agreement, and the state began administering the ARE again in June 1990. The agreement also established provisions for architects who passed the CALE and sought NCARB certification. Today, candidates are required to pass the California Supplemental Examination (CSE) in addition to the ARE.

Technology and Computerization

Soon after the launch of the ARE, another major technological shift was on the horizon: the computer. As architects began to replace drafting tables with computer programs, it was clear that the exam needed to evolve to keep up with practice. In the late-1980s, the Council began researching the feasibility and process of delivering a computer-based examination. One problem stood out: the design element of the exam.

NCARB volunteers once again partnered with ETS and its subsidiary, the Chauncey Group International, to design an entirely new approach to the 12-hour design exam. Their solution was a sophisticated, proprietary software system that would deliver individual graphic vignettes without favoring candidates who had practice using CAD systems in their offices.

“The computerized design examinations administered by NCARB in 1997 were recognized in the world of psychometric assessment as a breakthrough technological advance in the measurement of free-response, graphic solutions. … NCARB was considered a pioneer for the early adoption of cutting-edge testing theory and technology embraced by the ARE’s multiple-choice and graphic divisions.”

After several beta tests in the 1980s and early-1990s, the computerized ARE made its debut in 1997. It was a significant financial investment, and came with a somewhat unexpected drawback: now that candidates could take the exam any day of the week at a local test center rather than waiting for the once-a-year paper-and-pencil test, they seemed inclined to procrastinate. The number of candidates testing dropped significantly for several years following the launch of the computerized ARE.

After the computerized ARE launched in 1997, improved versions of the ARE were rolled out in subsequent years based on enhanced and expanded practice analyses: ARE 3.0 was introduced in 2004, followed by ARE 3.1 in 2006, and ARE 4.0 in 2008.

By 2011, NCARB faced another challenge: although cutting edge when it was first introduced, the graphic vignette software soon became difficult to keep up to date with what architects were using in their offices. The NCARB Board of Directors decided to press pause on its investment in maintaining graphic portions of the exam, focusing instead on researching new and easier to maintain options that could test minimum competency to practice without necessarily needing graphic-only divisions.

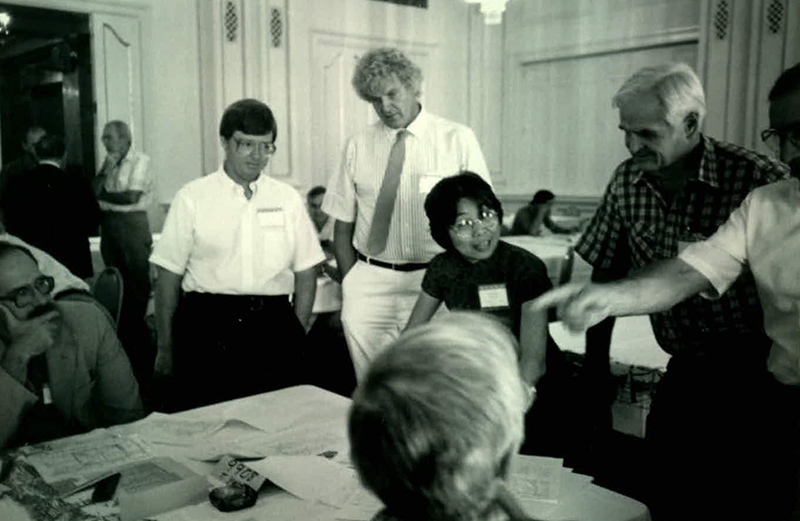

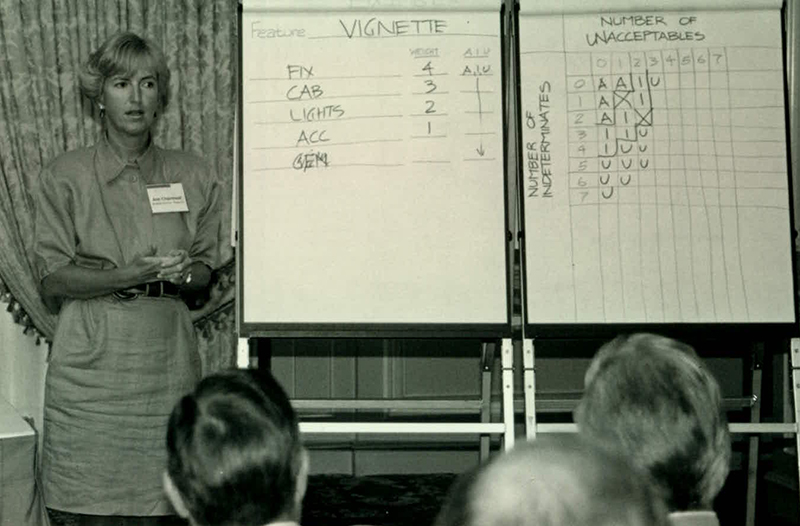

Ann Chaintreuil leads a discussion on the ARE in the 1990s.

ARE 5.0 debuted on November 1, 2016. The new examination was restructured into six divisions more closely reflecting the phases of a project. It also incorporated new graphic question types that could be easily developed and graded. Overall testing time was reduced from 33.5 to 25.5 hours. Candidates who were in the midst of taking ARE 4.0 when ARE 5.0 debuted were provided a dual administration window for 20 months to ease the transition between the two exams—as well as the opportunity to test in both versions and finish the exam in as few as five divisions.

“I consider the Architect Registration Examination to be NCARB’s greatest accomplishment in its 100 years. … The professionalism through which it was produced [and] the transformation to the computerized exam ... [has] been one of the greatest things that we’ve developed.”

Throughout the exam’s evolution, two things have remained constant: it has been developed by architect volunteers from across the country, and its objective is to measure competency to practice architecture that protects the health, safety, and welfare of the public.