Certificate History

The NCARB Certificate was created as a way to recognize applicants who met NCARB’s examination requirements. Over time, it evolved into a valuable credential with benefits including simplified reciprocity, free continuing education, and more.

VIDEO: HISTORY OF THE CERTIFICATE

Learn more about why the NCARB Certificate was established and how it has changed over time.

Establishing a Credential

The Highest Minimum Standard

Demand for architects in the United States began to increase dramatically following the Great Depression, and as more individuals sought to become licensed in multiple states, NCARB’s members were able to guide their boards toward uniform requirements that would simplify the complicated reciprocity process.

Examination remained the requirement with the widest variation; by using NCARB’s Standard Senior and Junior examinations to replace or supplement their own test, boards no longer needed to re-qualify out-of-state applicants. Soon, applicants who had met NCARB’s rigorous “highest minimum standard” were eager to have physical proof they could share with other boards or hang on a wall.

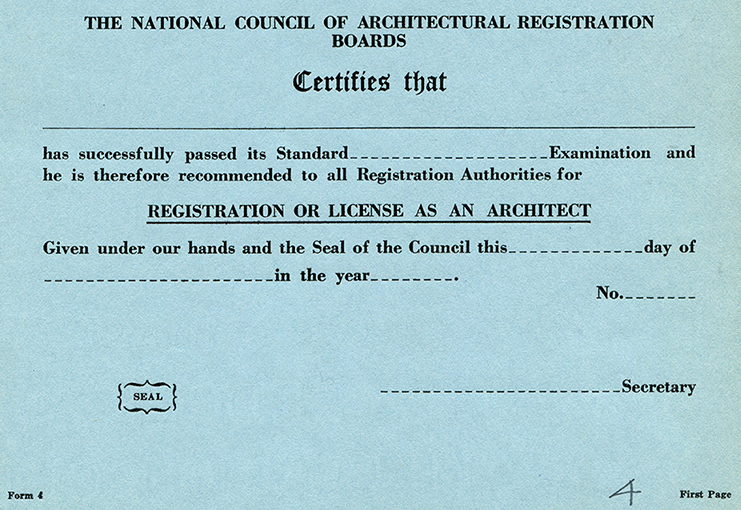

In 1936, NCARB created a Committee on the Form of the Certificate, and the resulting report was delivered at the 1937 Annual Meeting. After debating the boundaries of the Council’s responsibilities versus the boards’, the membership decided to issue the NCARB Certificate to individuals who had met NCARB’s education and experience standards (required for admittance to the exam) and passed the exam. The Certificate could be presented to a licensing board as proof that NCARB recommended the architect be approved for reciprocal licensure.

A gold seal was used for applicants who passed the Senior Examination and a silver seal used for those who passed the Junior Examination. In June 1938, the first Certificate was awarded to Nelson Spencer.

Updating Qualifications

Over the next several years, NCARB’s membership debated best practices for the Certificate—including tweaking the Certificate’s language and determining how and when an architect’s Certificate should be revoked. By 1949, there were well over 1,000 NCARB Certificate holders, and over a third of them were originally licensed in New York.

In the early-1950s, NCARB’s members began to question the “junior” versus “senior” designation, eventually deciding to remove the distinction and issue a single NCARB Certificate in 1955.

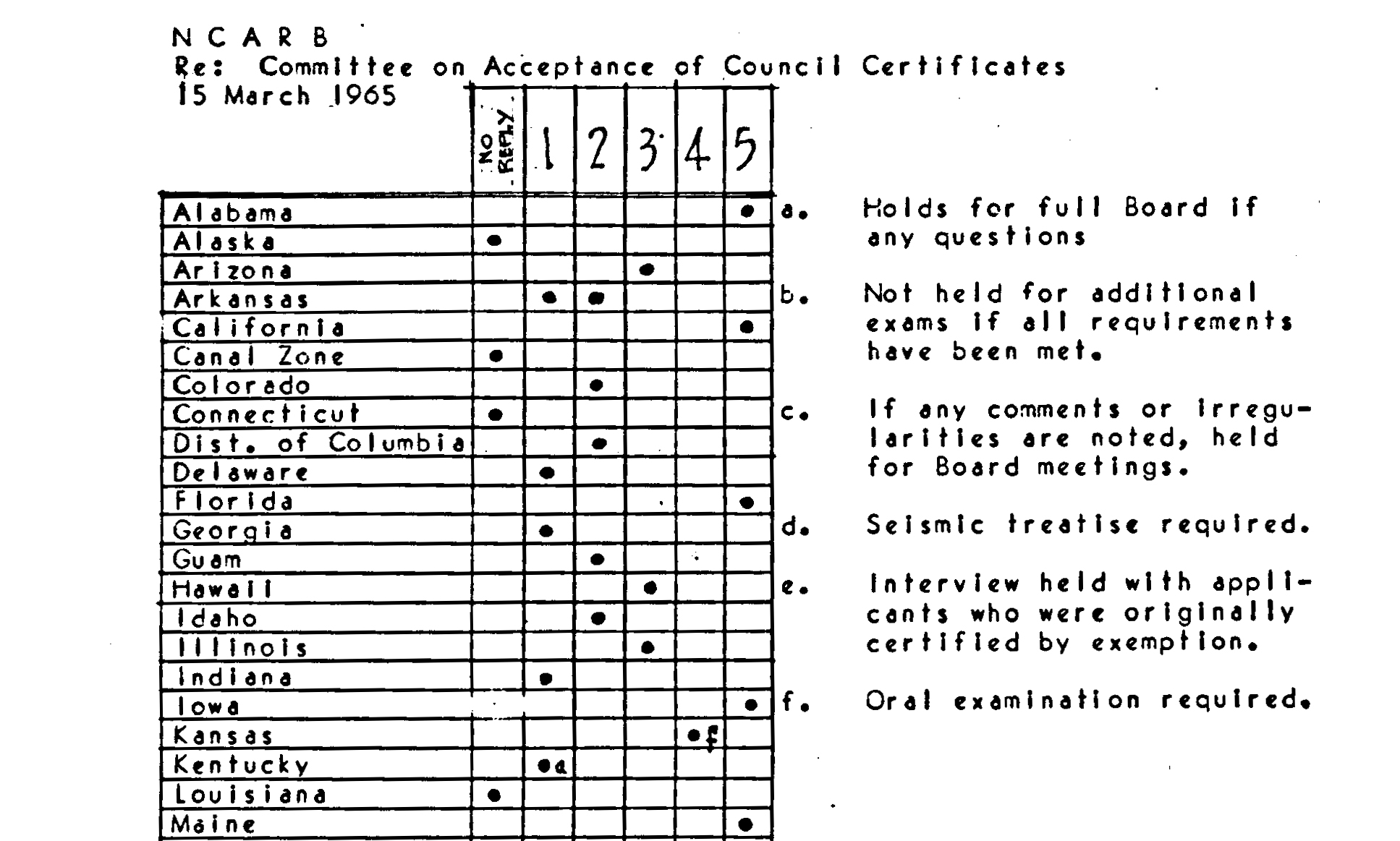

Throughout the late-1950s and 1960s, NCARB’s members repeatedly questioned the value of the Certificate—some boards felt the Certificate should be the only method of reciprocity, while others felt the Council’s standards were unfair to architects who lived in states with other requirements. This opened up a broader conversation about requirements, and Council leadership began to take a firmer tone toward encouraging boards to adopt NCARB’s standards.

As a result, more boards aligned their requirements to align to NCARB’s uniform standards, and the Certificate became a more useful and accessible means to reciprocity. Interest in the credential increased to the point that NCARB staff had difficulty keeping up with requests for certification and reciprocity.

Meanwhile, the organization began to uncover a flaw in the original Certificate system: in the 1930s, the credential was awarded for life (or for as long as the architect remained licensed in their state of initial licensure). This caused both practical and financial problems; boards couldn’t be sure a certified architect was still practicing, and NCARB’s income from the initial certification didn’t make up for the expense of maintaining and transmitting Records. To solve the problem, the Board of Directors instituted five-year reviews, when a Certificate holder would be asked to pay a small renewal fee and update information on file. Eventually, this became the annual renewal in use today.

“Great interest has been shown by architects in obtaining the Council Certificate in the past two years. Most architects can meet the requirements for admission to the Standard NCARB Examinations and the Certificate should be the goal of every registered architect.”

National Programs

Experience and Examination

The main issue preventing boards from wholeheartedly accepting the Certificate was the lack of national programs. With jurisdictions issuing their own exams—which were then evaluated by NCARB—boards didn’t always trust another jurisdiction’s exam to be equivalent, and the amount of experience required continued to vary.

In response, NCARB turned its focus away from reviewing exams and toward creating its own. The first truly national exam launched in 1963, and passage of NCARB’s exam subsequently became a requirement for certification. In 1968, members passed a motion requiring that all boards work to accept the NCARB Certificate for reciprocity after 1969 “as soon as it is practical for the states to do so.” After the launch of the Intern-Architect Development Program (IDP) in 1977, completion of the Council’s experience program also became a requirement for certification.

By 1980, only one of the three E’s remained outstanding: education. After years of back and forth regarding what level of education should be required for licensure and certification, a resolution requiring a degree from a National Architectural Accrediting Board (NAAB) accredited program finally passed, effective 1984. Procedures and Documents Committee chairman and future NCARB President Robert E. Oringdulph, of Oregon, briefly explained the reasoning behind the resolution: “I think it's important to note that we feel that the certification standard should be as close as possible to or equal to the highest standards set by the states. Many states are now requiring Bachelor of Architecture degrees, and in light of this, we feel that the certification process should bring itself up to at least a close level or the highest levels of the states.”

In spite of subsequent attempts to repeal the resolution, the requirement held.

Establishing the Education Alternative

Faced with a deeply divided membership, the Board of Directors agreed at the next Annual Meeting to study alternative pathways for applicants who lacked the required professional degree to remain eligible for the NCARB Certificate. The 1980 resolution implementing the degree requirement was amended in 1981 to include a provision for a “broadly experienced architect.” Two years later, the Council released The NCARB Education Standard to help those without the required professional degree understand what they needed to do to qualify for the NCARB Certificate. The Standard was based on the student performance requirement established by the NAAB to help potential certification applicants address any deficiencies in their education.

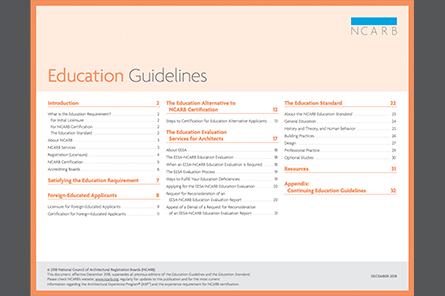

In 1984, NCARB hired a contractor to administer the Education Evaluation Services for Architects (EESA), a new service that carefully compared a nontraditional certification applicant’s education to NCARB’s Education Standard. If any deficiencies were noted, the applicant could compile a dossier to explain how their experience supplied the necessary knowledge. If the dossier and an interview with the candidate proved to be satisfactory, the Broadly Experienced Architect (BEA) Committee approved the applicant to receive the NCARB Certificate. Responsibility for the EESA program was eventually taken over by the NAAB.

NCARB passed a resolution in 2001 to simplify the BEA requirements and process and reintroduced the program. Two years later, the Council added a parallel program for foreign architects: the Broadly Experienced Foreign Architect (BEFA). The Council encouraged all Member Boards to adopt the education alternatives and arranged demonstrations of the dossier review process used to determine an applicant’s qualifications.

The outreach campaign helped to win converts to the education alternative. By 2013, over 45 jurisdictions officially recognized both the BEA and BEFA programs.

In 2014, the Council investigated re-engineering the BEA and BEFA processes to make them less time-consuming, less expensive, and more transparently objective. After the Board, volunteer committees, and staff studied the issue, Member Boards were presented with a proposal to phase out and replace the aging programs at the 2015 Annual Meeting. The resolution narrowly failed; after another year of study and tweaking, a revised proposal to create a “new education alternative” was accepted by the membership. The new alternative gave architects already licensed in a U.S. jurisdiction a convenient way to satisfy the Certificate’s education requirement—either by completing additional hours within the experience program, or addressing educational deficiencies by completing an online portfolio, documenting learning through experience.

“When you grant such a Certificate you are saying to your peers and colleagues in the profession ‘Here is a man worthy to practice architecture. We believe in him; we recommend him to you. We say you do not need to examine him again. We have done that, and he is worthy.’”

Adding More Benefits

Over time, NCARB and its members work to increase the benefits of the NCARB Certificate, making the credential more valuable to the nation’s architects. The first to be added was continuing education (CE), when a pilot monograph was distributed to Certificate holders in 1978-79. When the CE program really got off the ground in 1993, monographs remained free for Certificate holders.

And when NCARB Records moved online in the late-1990s and early-2000s, holding an NCARB Certificate became an even more streamlined, accessible way to maintain a secure professional history and earn reciprocal licensure. By the end of 2018, there were over 45,000 NCARB Certificate holders.